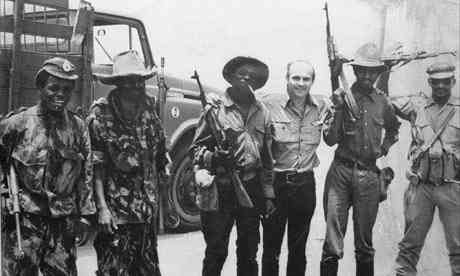

"Making the law even truer" ... Ryszard Kapuściński with soldiers in Angola, 1975. Photograph: PAP/CAF/EPA

Ryszard Kapuściński kept dual notebooks when he was on the road. One was for his pursuit as an group reporter, haring about the world, assembly deadlines and battling to record stories whose delivery was paid for out of the profession of meaningless comrade banking he perceived from Warsaw. The alternative was for his job as a writer, creation reflective, creative, mostly musical clarity out of what he was experiencing.

To brew the dual notebooks up is to miss the point of him. Artur Domoslawski"s book, from what is reported about it, suggests that Kapuściński was a prejudiced contributor who done up stories about events he hadn"t seen, and invented quotes. This is to upset his broadcasting with his books. Almost all journalists, solely for a handful of saints, do on arise whet up quotes or somewhat shift around times and places to worsen effect. Perhaps they should not, but they – we – do. A couple of of us go beyond the phonetic manners of what is tolerable, and send the writings watcher accounts of events we never saw since we were somewhere else. That, in the profession"s ubiquitous view, is right off the advance booking – not on.

But this is not the complaint with Kapuściński"s journalism. None of the doubts, as far as I can see, are about the despatches and facilities he sent to newspapers, or to the Polish Press Agency. They are about his books. The adventures and encounters he describes in his books are on a opposite turn of veracity. Like his crony Gabriel García Márquez, Kapuściński used to verbalise about "literary reportage". You"re meant to hold what you are being told, but not in each word for word detail. I think that any obvious publisher who does that has a avocation to have the eminence transparent to the reader, notice her or him that this comment is not headlines stating but one man"s notice of a law illuminated by imagination. Kapuściński did not have that eminence clear, and I instruct that he had.

A good e.g. comes in his best-known book, The Emperor. Kapuściński is on vacation Addis Ababa after the deposition and genocide of Haile Selassie, and interviewing old, fearful men who were his courtiers. In the book, they verbalise to Kapuściński in exquisite, roughly Biblical cadences, abounding in mocking item and displaying an astonishing laxity with horse opera modes of law and theology. It"s all somewhat as well good to be true. Did he amplify these speeches, or could they be wholly fictional? I think that what he did was to name from his notes, maybe shift the sequence in that things were said, dump passages that did not seductiveness him and afterwards refinement up the majority appropriate pieces for well read effect. What emerges in the book, and from these speeches, is the majority in contact with and divulgence comment of a justice – that roughly archaic establishment that once governed majority of amiability – I"ve ever read: wholly convincing, even if the reader can"t be certain that those were precisely the difference the courtiers used.

In the end, there is no floodlit handle limit in between novel and reporting. All we can demand on is that a well read content is not presented as a word for word transcript. Kapuściński all the time wandered behind and onward opposite that frontier, but regularly knew that side he was on at a since moment. Scrupulous in his journalism, in his books he was able of inventing in sequence to have a law even truer. He was a good story-teller, but not a liar.

No comments:

Post a Comment